BIEST

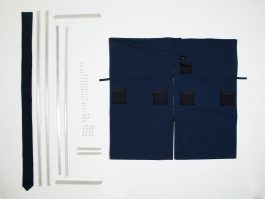

KIMONO 2.0

Photo: Palma Llopis/Nuphar Blechner

Long before their intense working visits to Japan began, BIEST had been looking into the composition, the structure, the perception of the self and the world, the workmanship and the thinking that is condensed into and with a piece of material such as the kimono. With the Kimono 2.0 series they have undertaken a translation, an adaptation and an update by linking their own questions to the kimono’s long tradition.

In the “Empire of Signs” – his reflections on a country he calls Japan; focusing more on signs and symbolic meaning than descriptions of reality – Roland Barthes writes about the relationship between an object and the space surrounding it. “It is as if the object frustrates, in a manner at once unexpected and pondered, the space in which it is always located. For example: the room keeps certain written limits, these are the floor mats, the flat windows, the walls papered with bamboo paper (pure image of the surface), from which it is impossible to distinguish the sliding doors; here everything is line, as if the room were written with a single stroke of the brush. Yet, by a secondary arrangement, this rigor is in its turn baffled: the partitions are fragile, breakable, the walls slide, the furnishings can be whisked away, so that you rediscover in the Japanese room that ‘fantasy’ (of dressing, notably) thanks to which every Japanese foils – without taking the trouble or creating the theater to subvert it – the conformism of his context.”

A Japanese kimono is flat – in an unusual way it defies body and space and yet knows it is determined by and in them – it is a “pure image of the surface” – its pattern continues without interruption from the back to the sleeves all the way down to the front seam. This means it ultimately appears like a painting, a single brush line. It refers to nothing but itself – it can envelop a body, it can even adapt to each individual body without severe adjustment to its cut. But it does not need a subject, it does not want to create one. It is the opposite of the Western ready-to-wear concept and yet at the same time is an ideal example of it. It takes each body (into itself) by folding, lacing, gathering and draping.

Is an individual person packaged within? The question is irrelevant. It’s the “packaging” that characterises human activity, not the content. A kimono cannot be put on alone; that it has been put on means that there was “preparation” by banning absence … in doing, not in being.

BIEST’s experimental layers and wraps, asymmetries and deconstruction are also inspired by Japanese kimono; the fabric panel is also draped around the body. The clothing is not chiefly designed to present an ideal body image, instead it is an adaptable shell. The first thought that goes into the design of “Western clothing” is the shape it adopts when worn, which is why three-dimensional design drafts (using extremely idealised figurines) are usually the starting point. Behind a kimono, however, is a very different approach. The clothing, not the wearer, is at the centre, the shell (without centre) itself, that knows how to become a piece of art.

A kimono equalises a body, perhaps it even equalises a subject, individuality. This can be considered contrary to the paradigms of Western fashion. BIEST’s approach also uses wide and thick cotton weaves with gatherings that seem purely coincidental and similar to folds. Unusual drapings that only reveal themselves on closer inspection, loose threads hanging from the lower seams, plain colours: black, navy blue and in exceptional cases a combination of both plain colours… All of this emphasises that other questions are more important here. A celebration of shells, envelopment, outline.

While Issey Miyake said in the early 70s that he designed clothes with the goal of wrapping the body in just “one piece of fabric” and deconstructing the human silhouette – as an alternative to tailoring accentuated by and accentuating the body – BIEST is now striding forward with a new understanding of body, of space, of ready-to-wear, flexibility and ecology. BIEST’s kimono offers both a shell and, when needed, revelation. It shows itself and its wearer as they so wish. It does not disguise its functionality. It provides the hidden and hiding place as desired. It provides transparency, surfaces, flatness, but also contours, limits, space and presence. It allows disappearance and appearance at the same time.

When Barthes writes that “the richness of the thing and the profundity of meaning are discharged only at the price of a triple quality imposed on all fabricated objects: that they be precise, mobile, and empty”, BIEST finds deep links to its own work and questions in the Japanese understanding of emptiness and precision, potential and mobility. BIEST’s clothes are all line too, a performance in embracing tension. One might wish to add Barthes’ words: “without taking the trouble or creating the theater to subvert it – the conformism of his context,” although the paradigms of the Western approach to fashion and today’s clothing industry certainly merit some kind of subversion.